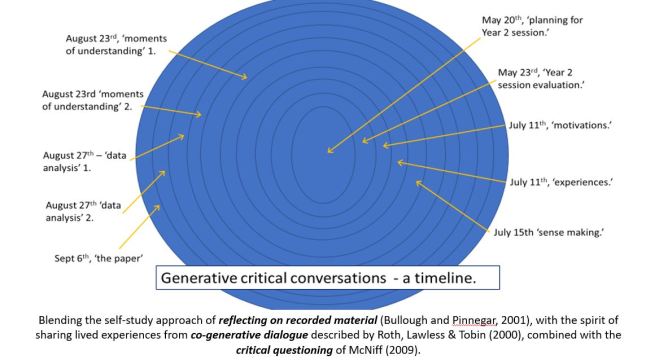

The theme of ISBE 2019, hosted by Newcastle and Northumbria Universities, was ‘Space’, and the idea was to share and discuss findings and lessons from research to influence the worlds of academia, policy, practice. Sounds pretty standard conference agenda stuff. But what ISBE 2019 did was more powerful, and much needed. From the diverse and provocative opening panel, brilliantly facilitated by new ISBE President Kiran Trehan, to the challenging and more socially aware conversations in and around the enterprise education track, the tone of the conference felt more relevant and engaged than I had previously experienced. Here’s three things I’m still thinking about… 1. Setting the tone… This is the fifth ISBE I’ve attended, and I must admit that sometimes I’ve experienced it as an alternate universe, somewhat disconnected from the reality I’m experiencing. My enduring memory from last year’s panel was a conversation about failure, and that phrase ‘fail fast, fail often’ was deployed to characterise how entrepreneurs should approach business life and death. I’ve run a business since 2013, and there have been times of financial jeopardy, not least when big organisations such as universities and Local Enterprise Partnerships have taken so long with contracting and payment that I’ve had sleepness nights thinking: is next month going to be the month that I go bump? As a divorcee, mortgage payer and mother of two dependents, the bravado of failing fast and often just doesn’t chime. I prefer Allan Gibbs view that there is huge tenacity and inventiveness in survival, especially when people face practical, social and material constraints beyond their control. Whilst I was braced to repeat the experience – of not feeling represented during the panel discussion – it started to become clear that this panel was not going to be more of the same. First, the panel was diverse, not just in social make-up, but in philosophy. Yes, there were go-getting entrepreneurs and pragmatic policy makers/politicians, but there were also critical scholars, articulating the kinds of frustrations that better reflect the world I feel I observe. There was Kiran Trehan’s challenging opening; demanding reflection and critique from the panel and the audience. And then it started: talk of inequality, class and intersectionality. Monder Ram asked the audience: why don’t we provide courses on entrepreneurship and inequality, where’s the professorship in entrepreneurship and inequality?’. Then Susan Marlow told the audience: ‘if we keep doing this dance around inequality, we’re giving a massive excuse pass to those who facilitate unequal structures.’ By this point I was exchanging astonished looks with colleagues and tweeting that #ISBE2019 ‘has had a personality transplant.’ Kiran Trehan asked delegates to consider: is what we are doing supporting the status quo, or challenging the status-quo? Personal responses to that kind of question will be somewhat related to whether or not the status quo is working out well for you or not. For many, many people, the status quo is iniquitous and precarious. Risk and uncertainty has been passed on to individuals through the gig economy. The widely promoted idea that everyone is an entrepreneuring-homoeconomicus and the pervasive philosophy of competition and market ideals has weakened values of collective responsibility, cooperation and kindness. It strikes me as odd why the entire research community isn’t more interested in these kinds of issues. Seeing such issues as something for the critical track limits the thoughtfulness needed to illuminate the role of research in reproducing such ideas, and the effects which can transpire from them. But opening the conference with this panel, talking about these things, created space for such issues to be drawn into track discussions. As someone said in the enterprise education track ‘I’ve never heard the word class uttered at ISBE before, and now I’ve heard it from the opening panel and in this room.’ Certainly, in the enterprise education track, this opening set the tone for more critical discussions, more challenge and more reflection than I have witnessed before. Long may it continue. 2. Aspirations vs Expectations… Emboldened by the critical opening to the conference, there were more in-track conversations about the role that individual and social context might play in how enterprise and entrepreneurship education impacts different people in different circumstances. A conversation around student ‘aspirations’ to start a business got me thinking about a side project I’m working on with Jakob Werdelin for HeppSY, about developing confidence and resilience in a Widening Participation context. In WP, the ‘aspiration raising’ discourse has been effectively challenged as unhelpful for the very students one might most hope to support. Harrison and Waller (2018), argue that asking students about their aspirations (in the WP case, to go to university, but we could translate their insights to the example of starting a business), is unhelpful because across the board, student aspiration is generally high. They de-bunk the ‘poverty of aspiration’ discourse as not reflective of what young people would like for themselves. They argue that young people, across social classes, do aspire to do well, so continuing to speak of low aspirations does not reflect the real issue at play. They say it would be more helpful for the student (and useful for researchers), to ask about ‘expectations’. This change in focus might illuminate the sorts of social and material obstacles that are actually at play in the different rates at which students progress to university. After all, what you’d like, and what you expect are two different things. I’d like to win the lottery, but don’t expect to. A student might like to go to university, but financial constraints, family and caring obligations, or the felt pressure of needing to start earning a living means they don’t expect to go. Equally, a student might very much like to start a business, but may not expect to because of any number of practical and material reasons. In the project I’m working on, we are building in touch points where activities intentionally try to understand such obstacles, so that educators are aware, and can act on, the kinds of constraints that stop WP students fulfilling their aspirations. In one activity we ask students to consider a time or situation where they wanted something to do or be something, but it didn’t happen, and then identify the practical obstacles that got in their way. Such an exploration has the potential to surface the material constraints which hold students back, rather than focussing attention on aspiration. There is still a way to go before issues of practical and material disadvantage are explored in the sort of depth that is happening in a field such as WP, where the focus is on bringing the greatest benefit to those who most need it. But there is much to be learned from such a field, and other critical scholarship, if the goal of challenging the status quo is to be pursued. In the enterprise education track we could do more to ask ourselves, how does a students’ social background play in to how much they survive, thrive or sink in the activities we provide? And what assumptions do we make, as enterprise educators, when we’re planning and teaching enterprise education? Which brings me to my final thought. 3. Generative Critical Conversation… The work myself and my co-author Jen Huntsley presented was around our paper ‘Creating Space to Question’, and in particular, we shared a method we developed through our research process, which we are calling Generative Critical Conversation. In the immediate context of our study (where we worked together to co-develop and co-teach a more critical introduction to enterprise education for trainees on a primary education/QTS course at the University of Huddersfield), we used these conversations to develop a deeper understanding of what comes into play when educators get together and plan what they do. In teacher development, there is an idea of co-generative dialogue, where teachers gather to talk about what has happened in a lesson or intervention. The approach is productive, it’s intended to improve teaching strategies, subject specific pedagogy, as well as teaching and learning more generally. An important element is the sharing of lived experiences and creating a forum where successes and failures are raised and analysed. Another teacher educator, Jean McNiff, demands that asking critical questions should be central to teachers development, so her questions – What are we doing? Why are we doing it? What difference are we trying to make? – supplemented our method. Our study involved recording a generative, critical conversation, then listening to the conversational artefact separately, and then recording another joint conversation to critically interrogate and try and understand our assumptions and preoccupations. Related to Kiran Trehan’s challenge to ISBE participants to be more reflective, there is a persistent concern in enterprise education that educators lack criticality and unquestioningly adopt taken for granted practices (Fayolle, 2013; Fayolle & Loi, 2018). This is the broader context for mine and Jen’s study and our work relates to it on two levels. Whilst we intentionally tried to develop an intervention for primary trainees which facilitated them to question taken-for-granted practices in enterprise education, our process of working together also created space for us to question our work and ourselves. Both Jen and I agreed that the conversational artefact was crucial in this process – being able to go back and listen surfaced where we were misunderstanding each other, or pursuing our own pre-occupations, or getting carried away on a wave of enthusiastic creativity. The space between conversations, where we listened to ourselves and each other, and asked critical questions about what we heard, enabled a deeper appreciation of our assumptions and how they might relate to our biographies and social and societal location. Creating space to question doesn’t mean turning into an unproductive troll, unable or unwilling to take forward enterprise education. The ‘generative’ part of Generative Critical Conversations, keep things productive, with a focus on improving and refining practice; the critical part encourages us to ask questions about what we’re doing and why we’re doing it and explore where good intentions might lead to unintended consequences. We suggest that such a method helps address Jean McNiff’s ultimate critique, that too often people’s practice is theorised for them, and instead we should be encouraging educators to learn about and theorise their own practices for themselves. Perhaps this is why we felt we managed to develop a critical introduction to enterprise education which did not render trainees as unwilling sceptics (Rönkkö & Lepistö, 2015), but pursued a ‘revitalizing’ agenda (Berglund & Verduyn, 2018). In our paper we describe how McNiff argues that The Academy is not a faceless institution, but colleagues, real human beings, with the capacity to think and exercise transformative power, with agency to develop practices which contribute to a peaceful, productive, socially just world. This year, more than any other, ISBE felt like a place where that could happen. Here’s hoping that spirit continues to develop in Cardiff in 2020.

Home

Three Thoughts after ISBE 2019 Nov 17, 2019